When nature restoration reduces disease risk and when it doesn’t

Nature restoration is increasingly seen as a win–win solution: restoring biodiversity, tackling climate change, and improving human health simultaneously. Across Europe, ambitious restoration targets are being rolled out through national strategies and the EU Nature Restoration Law. But does restoring nature always reduce the risk of infectious diseases?

A new study published in Nature Sustainability by the team from the University of Stirling and Alternet suggests the answer is more nuanced.

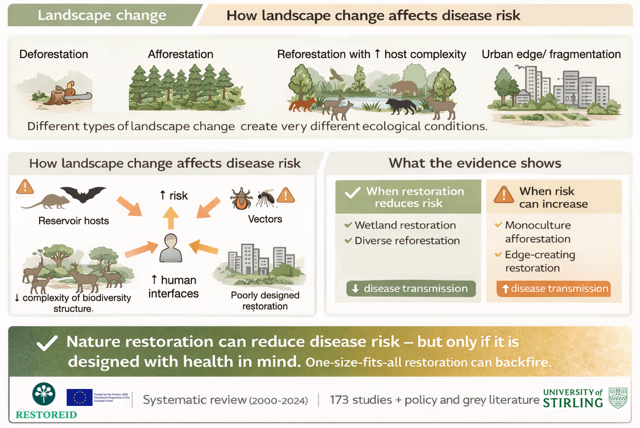

A common assumption in policy and public debate is that increasing biodiversity, for example, through reforestation or ecosystem restoration, automatically reduces the risk of zoonotic diseases. While this can be true in some cases, our research shows it is not universal.

By synthesising evidence from a wide range of ecosystems and regions, the study demonstrates that the health outcomes of restoration depend strongly on how, where, and in what context restoration is carried out.

In many countries, restoration policies are advancing faster than the scientific evidence needed to understand their potential impacts on disease risk. This gap matters because poorly designed interventions can sometimes lead to unintended consequences.

What the evidence shows

The study highlights several key findings:

- In many contexts, increased biodiversity is associated with reduced disease transmission, a phenomenon often referred to as the “dilution effect”.

- However, certain types of restoration that increase forest edges, particularly afforestation and reforestation in simplified or human-dominated landscapes, can increase contact between wildlife, livestock, and people.

- These increased contacts can, under specific conditions, raise the risk of zoonotic disease transmission rather than reduce it.

- Outcomes depend on land-use patterns, local ecology, and the biology of the pathogens and host species involved.

Why this matters

As countries scale up restoration across forests, agricultural landscapes, wetlands, and peri-urban areas. These efforts are essential for biodiversity and climate goals, but they also intersect with human and animal health.

Our findings suggest that restoration strategies should:

- move beyond one-size-fits-all approaches

- explicitly consider health risks and benefits at the planning stage

- integrate ecological, agricultural, and public health data

- involve local communities in restoration design

Towards risk-sensitive restoration

The research points to practical ways forward:

- designing restoration projects that reduce high-risk human–wildlife contact

- avoiding the creation of habitat edges that favour disease reservoir species

- embedding One Health thinking into restoration planning from the outset

Rather than questioning restoration itself, the study reinforces the need for risk-sensitive, evidence-based restoration that maximises benefits for biodiversity and climate while minimising unintended health impacts.

This work directly supports the goals of the RESTOREID, which aims to help policymakers and practitioners make informed restoration decisions that account for infectious disease risk. The findings are already feeding into decision-support tools and policy guidance.

As restoration efforts accelerate across Europe and beyond, the key question is no longer whether nature can help protect human health, but how to design restoration that does so safely and effectively. By grounding restoration in robust evidence and a One Health perspective, we can ensure that nature-based solutions truly deliver on their promise.

Read the full study in Nature Sustainability (Author Accepted Manuscript available Open Access at the Stirling website and on ResearchGate) - DOI 10.1038/s41893-025-01750-2