Fieldwork in Lulanda: Exploring the Role of Restoration in Reducing Zoonotic Disease Transmission

By Baraka Edson, PhD student.

From June to July 2024, the RESTOREID project initiated a field study in Lulanda, Tanzania, focusing on understanding how landscape restoration impacts zoonotic disease transmission. RESTOREID (Restoring Ecosystems to Stop the Threat of Re-emerging Infectious Diseases) aims to explore how healthier environments, shaped through landscape restoration, can mitigate the risk of zoonotic diseases, bridging the gap between biodiversity, public health, and conservation efforts. This will aid in creating effective early monitoring systems and innovative strategies for sharing information both locally and globally.

Executive Summary

The goal of this research is to investigate how biodiversity degradation and restoration affect the dynamics of zoonotic disease transmission, specifically among small mammals, their ectoparasites, and mosquitoes. The study spans four key patches: Fufu Forest (82.6 hectares), Mgwilwa Forest (84.3 hectares), Corridor (54 hectares), and surrounding farms. By comparing degraded and restored areas, the study will help identify environmental and biological factors that either reduce or amplify disease spread, providing insights for better public health strategies and conservation efforts. The findings will help guide policies that link ecosystem restoration with zoonotic disease prevention.

Fufu Forest and the Corridor

In Fufu Forest and Corridor the team focused on the varying degrees of forest restoration. Both patches hold significant ecological value as wildlife habitats, yet they face threats from human activities such as agriculture.

Image 1: The Fufu Forest and the Corridor, key sites of biodiversity monitoring.

Mgwilwa Forest

Mgwilwa Forest, on the other hand, has seen more severe degradation due to encroaching agricultural activities. The impact of this disturbance is crucial to understanding how restored landscapes can offer refuge for wildlife and limit zoonotic disease risks.

Image 2: A glimpse of Mgwilwa Forest, showing signs of human impact.

Trapping and Monitoring Wildlife

The team employed various methods to capture and monitor species in the study areas. Sherman and Victor traps were set up to capture rodents, while mist nets were used to safely capture bats for study. Flies were also collected for environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling, which can reveal important details about biodiversity.

Image 3: Sherman and Victor traps used to capture small mammals for disease monitoring.

Image 4: Carefully removing a bat from the mist net, ensuring minimal disturbance to the animal.

Image 5: Setting traps to capture flies for eDNA analysis, providing insight into the area’s biodiversity.

Listening to the Forest: AudioMoth Technology

To assess the biodiversity of animals in Fufu and Mgwilwa forests, as well as the Corridor, the team employed AudioMoth devices. These devices capture soundscapes to monitor species diversity, which is directly linked to understanding disease prevalence in the area.

Image 6: The AudioMoth device, used to record animal sounds in the forests and corridors.

Collecting and Storing Samples

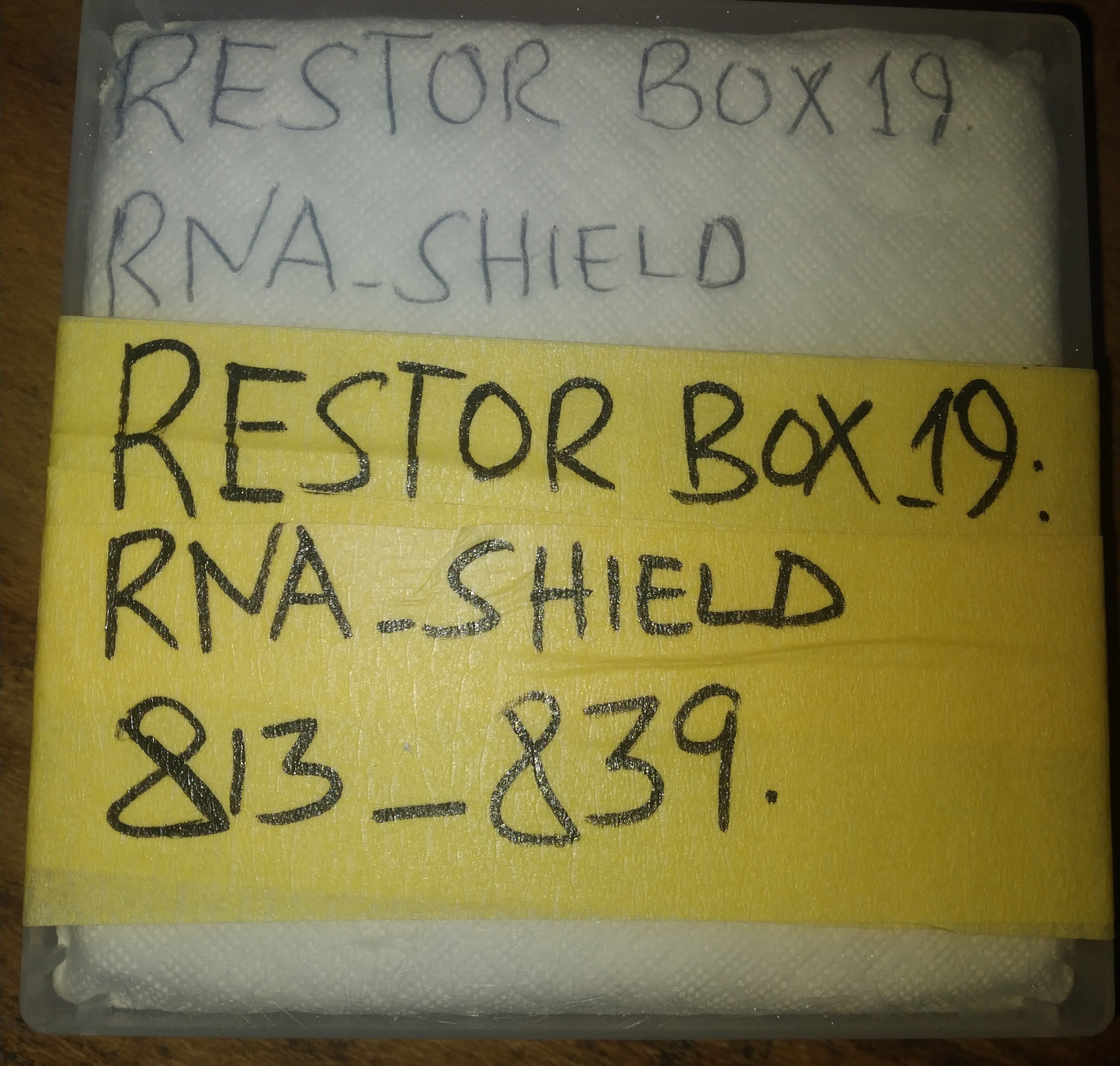

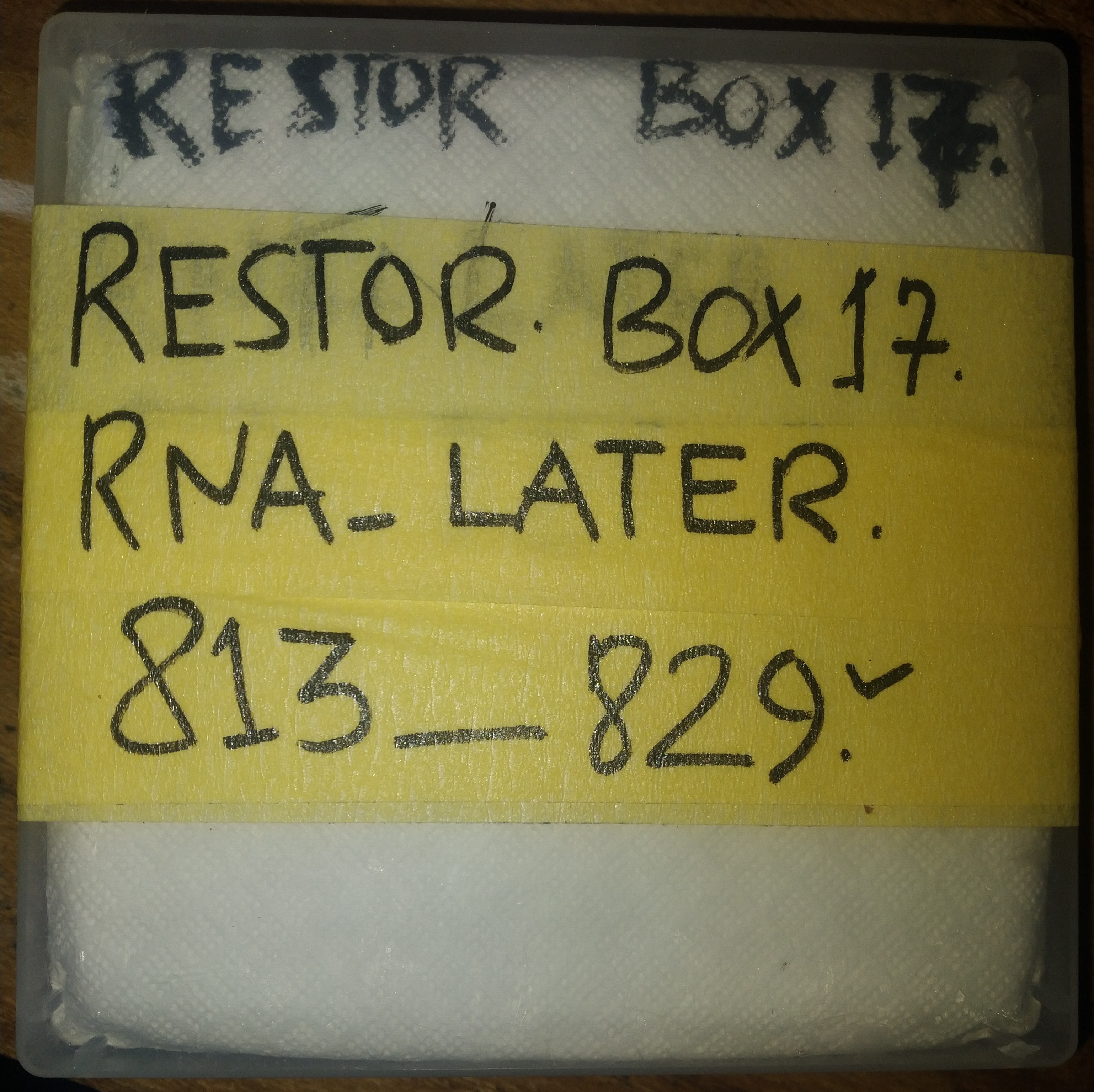

Field experts donned protective gear as they collected samples from small mammals. Samples were carefully preserved in RNA later and RNA shield solutions, transported in cool boxes, and stored in a portable -20°C freezer to ensure the integrity of the biological materials.

Image 7: The sample collection team preparing for fieldwork, equipped with protective gear.

Image 7 & 8: Sample collection from small mammals.

Image 9, 10 & 11: Samples being stored in RNA solutions before being transported in cool conditions for further analysis.

Data Documentation and Final Steps

Throughout the field activities, both soft and hard copies of data were diligently recorded, ensuring that all findings were documented for later analysis. After days of trapping, the team gathered for final checks and reviews of their field efforts.

Image 12: Data documentation, crucial for maintaining accurate records of sample collection and biodiversity observations.

Image 13: The field team, after completing a successful round of trapping and sample collection.

Conclusion

This initial fieldwork marks a significant step forward in the RESTOREID project’s goals of understanding how restoration can be harnessed to reduce the risks of zoonotic disease transmission. The insights gained from the biodiversity assessments and pathogen sampling will be invaluable in shaping public health strategies and conservation policies aimed at integrating ecosystem restoration with zoonotic disease prevention.

Stay tuned as we continue our efforts, expanding our research in Tanzania to develop healthier environments for both wildlife and communities!